MedFriendly®

Polymyalgia Rheumatica

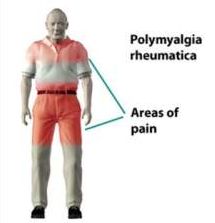

Polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR) is a disorder characterized by

inflammation, muscle stiffness, muscle tenderness, and muscle

aches and pain, particularly in the joints, joint linings, and sacs

(known as bursae) around these joints. Presence of these

symptoms in the shoulder is usually the first to occur. In other

cases, symptoms in the neck and hips occur first. Symptoms can

also occur in the pelvic muscles, thighs, buttocks, lower back,

hands, and upper arms. The fluid filled covering surrounding

tendons can also be inflamed. Tendons are groups of fibers that

attach muscles to a bone.

FEATURED BOOK: Polymyalgia Rheumatica: A Survival Guide

The pain and stiffness in PMR is usually moderate to severe. Both sides of the body are

usually affected equally within a few weeks after symptoms being, although at first,

symptoms may begin on only one side of the body. The stiffness and aching tends to

occur in the morning (e.g., when awakening) or after sleeping but improves as the day

goes by. These symptoms also occur due to being inactive for long periods (e.g., a long

period of sitting or riding in a car) and are associated with decreased range of motion in

affected areas.

Stiffness after periods of inactivity is known as gel phenomenon. Stiffness can also occur

after prolonged periods of activity. Pain and/or stiffness in the knees or wrists are less

common body areas affected. Symptoms come on acutely (suddenly) in about half of

patients, such as overnight, but usually over a few days or weeks. In other cases, the

pain comes on gradually and can occur in the evenings.

"Where Medical Information is Easy to Understand"™

WHAT OTHER SYMPTOMS AND SIGNS OCCUR IN PMR?

Other signs and symptoms of PMR can include loss of appetite,

depression, unintentional weight loss, a general feeling of not being

well (known as malaise), mild fever, sleep disruption (e.g., due to

stiffness or awakening at night due to pain), fatigue (sometimes to

the point of exhaustion), depression, and anemia.

Anemia is a condition in which there is an abnormally low amount of

hemoglobin in the blood. Hemoglobin is substance present in red

blood cells that helps carry oxygen to cells in the body.

Sometimes, the signs and symptoms of PMR can limit or prevent completion of activities of daily living

such as dressing, hygiene (e.g., bathing), grooming (e.g., hair styling), mobility (e.g., getting up out of bed,

couch, or car, standing up from a chair, turning over in bed), and social interactions. These problems are

caused by stiffness, aches, and pains, such that it can make it difficult to do things like bending over and

putting socks or shoes on or putting clothes on the upper body. Some doctors state that muscle weakness

is not a feature of PMR but the muscles can appear weak due to pain and muscle tissue loss, especially if

untreated. However, muscle strength is generally normal with no loss of muscle mass when the condition

begins.

About 15% of patients with PMR develop carpal tunnel syndrome. Carpal tunnel syndrome is numbness,

tingling, and pain in the thumb, index, and middle fingers, which usually worsens at night. Rarely, people

with PMR will experience high spiking fevers. When this happens, it should prompt a medical evaluation

for infection, vasculitis (inflammation of blood vessels), or another serious abnormality. Vasculitis has

traditionally been considered to be rare in PMR but it may be present more often than is currently realized

in the lower extremities. This is because it has been found that patients with PMR are at increased risk for

claudication (which may be caused by vasculitis). Claudication is impaired walking, pain, tiredness, or

discomfort in the legs that occurs during walking and improves with rest. A quarter of patients with PMR

have arthritis. Arthritis is an inflammatory condition of the joints, which is a place where two bones contact

one another.

WHO TENDS TO DEVELOP PMR?

PMR is twice as common in women than men. PMR most often occurs in people over the age of 60 to 65,

with the average age of onset being 70 (with some studies saying 72). It rarely, if ever, occurs in people

younger than age 50 and is more likely with increasing age over 50. In the U.S., 52.5 of every 100,000

people who are 50 years or older develop new cases of PMR. Less than 1% (0.5 to 0.7%) of the U.S.

population has PMR. However, about 2% of the population over age 70 have PMR.

There are increasing rates of PMR in northern countries. People of northern European descent (e.g.,

Caucasians) are more likely to have PMR than people of other ethnicities. Scandinavians are quite

vulnerable to develop PMR. About 1 in every 2000 people over age 50 in Sweden and Minnesota will

develop PMR. About 1 in every 133 people over age 50 in Minnesota have PMR. PMR rates are lowest in

Asians, Africans, and people of Middle Eastern descent. Patients in Mediterranean countries are also of

lower risk for developing PMR. For example, there are 12.7 new cases of PMR diagnosed each year for

every 100,000 persons.

WHAT CAUSES PMR?

The exact cause of PMR is unknown but it is believed that some people inherit a genetic predisposition to

develop the disease. There is evidence that two or more genes are involved in causing PMR. Genes are

units of material contained in a person's cells that contain coded instructions as for how certain bodily

characteristics will develop. Cases have been identified where PMR has clustered in families (e.g.,

passed down from generation to generation, present in siblings). One known risk factor for developing

PMR is having a gene type known as HLA-DR4, which is present twice as often in patients with PMR than

in those who do not have the condition. However, the strength of the association between PMR and this

gene type differs from study to study.

A genetic predisposition to developing PMR may interact with an environmental stressor such as a virus

that eventually causes the disease to manifest by activating monocytes. A monocyte is a relatively large

type of white blood cell with one nucleus (control center). The activation of monocytes is thought to

produce cytokines that then result in symptoms of PMR. Cytokines are proteins that play an important role

in inflammation. Types of cytokines known as interleukin-1 (IL-1) and tumor necrosis factor alpha have

been weakly associated with PMR. In Spain, a type of cytokine known as interleukin-6 (IL-6) was

associated with PMR symptoms in patients with giant cell arteritis (see last paragraph of this section). IL-

6 is often elevated in PMR and is probably responsible for the inflammation that occurs throughout the

body in PMR. However, the test for IL-6 is not available in most laboratories. Symptoms of PMR are

known to decrease when IL-6 levels decrease. There is not enough data on other interleukins to draw

strong conclusions between them and PMR at this time. A type of protein known as RANTES was also

associated with PMR in this population.

The inflammation in PMR is thought to begin in the sacs and lining around joints when an unknown antigen

is recognized by macrophages and dendritic cells. Antigens are substances in the body that can produce a

defensive reaction by the body. Macrophages are types of white blood cells that engulf and digest (eat)

harmful substances in the body. Dendritic cells are cells that process antigen material and present it to the

body’s immune (defense system). T-cells are also activated in PMR. T cells are a type of white blood cell

that directs the body s immune system to defend against bacteria and other harmful cells.

The viral theory is partly based on new cases of PMR being known to occur in clusters of the general

population. While there is no specific virus known to cause PMR, several common viruses have been

suggested as possible culprits. Examples include adenovirus (which causes infections of the respiratory

system), human parovirus B19 (a virus that causes various conditions in children and adults), and human

parainfluenza virus (a flu virus that affects the respiratory system). An infectious disease cause may

explain sudden onset of symptoms. Food sensitivities have been suggested as another cause of PMR.

White blood cells are known to attack the joint linings in PMR (especially of the shoulders and hips),

causing activity of inflammatory cells and proteins that are usually part of the body’s immune (defense)

system. White blood cells are cells that help protect the body against diseases and fight infections. The

inflammatory activity in PMR is focused on joint tissue. In some rare cases it is believed that cancer

stimulates the immune system to cause PMR symptoms.

Some people believe that PMR is the same condition as giant cell arteritis (which may be why the

conditions often co-occur), but manifesting in a different form. However, others believe that these are

separate conditions. Giant cell arteritis (also known as temporal arteritis) is an inflammatory disorder of

blood vessels (usually in the head and frequently in the temple area) which can cause symptoms such as

headaches, jaw pain, scalp tenderness, and visual problems (including permanent vision loss). About 15 to

30% of patients with PMR have giant cell arteritis and about 40 to 50% of patients with giant cell arteritis

have PMR. There is some evidence of injury to the thinnest layer inside of the blood vessels (known as

the tunica media) in affected muscle groups in patients with PMR.

HOW IS PMR DIAGNOSED?

PMR is typically diagnosed by a medical doctor who gathers a history, completes a physical exam, and

orders tests. Although there are no definitive signs or symptoms of PMR, supportive physical exam

findings would be limited range of motion in the shoulders (which can be due to pain, stiffness, and/or

shortening of a muscle or joint), neck, upper arms (e.g., difficulty lifting the arms above the shoulders), a

fatigued appearance, and other areas and inflammation of the wrists or hands. However, PMR usually

does not cause swollen joints. However, swelling (edema) of small joints in the wrists, hands, and/or

knees can occur in about 12% of patients. Some patients may complain of swelling in the arms or legs. In

some cases, if you press your finger against a part of the body affected by edema, it will make an

indentation in the skin that will flatten out as the fluid returns back to that area. When this happens, it is

known as pitting edema.

The type of doctor who makes the diagnosis of PMR is often a rheumatologist, which is someone who

specializes in inflammatory disorders of the muscles and skeletal system. However, family practitioners

also help manage the condition by trying to prevent conditions such as bone loss, high blood sugar levels,

and heart disease (see treatment section).

Blood tests

Although there is no specific definitive test used to diagnose PMR, blood tests are ordered in the

diagnostic workup. The two blood test readings of most value are C-reactive protein (CRP) and the

erythrocyte sedimentation rate (known as the sed rate), the levels of which may go up and down together.

High levels of CRP indicate increased inflammation. The sed rate is the speed by which red blood cells

settle to the bottom of a column of blood in a glass tube. Red blood cells are cells that help carry oxygen in

the blood. The reason that the doctor will want to check the sed rate is because certain inflammatory

conditions can increase the speed by which the red blood cells settle to the bottom of the tube. The farther

the red blood cells have fallen (measured in millimeters an hour or mm/h), the more the inflammation, and

the higher the sed rate value. Sed rate levels in PMR are usually high and over 40 mm/h.CRP and sed

rate levels can be very high in PMR (e.g., sed rate level over 100 mm/h) but in some cases they are only

slightly elevated, and sometimes they are normal. For example, the sed rate is mildly elevated or normal in

7 to 20% of PMR patients. This tends to occur in patients with mild forms of PMR. In such cases, relying

on a quick improvement in response to corticosteroids will be more helpful in the diagnostic process.

Studies that follow patients with PMR symptoms over time indicate that CRP may be a more sensitive test

for the diagnosis of PMR than the sed rate. This is also true for patients with mild forms of PMR. However,

other studies indicate that the sed rate is the more sensitive test. While checking the C-reactive protein

and sed rate are helpful in the diagnostic work-up, the values of these tests can be elevated for many

other reasons besides PMR.

Blood tests for muscle enzymes are unhelpful as these are normal in PMR. An enzyme is a type of protein

that helps produce chemical reactions in the body. For example, creatine kinase levels are normal in

PMR, which helps distinguish it from other types of muscle diseases. Creatine kinase is an enzyme found

in the muscles, brain, and other tissues that helps store energy. Checking the red blood cell and platelet

count is common in the diagnostic work up of PMR. Platelets are cells that help change the blood from a

liquid to solid form. People with PMR often have very high levels of red blood cells and platelets (with the

latter reflecting inflammation). However, many people with PMR also have low levels of red blood cells.

White blood cells counts may be mildly increased or normal in PMR. Levels of antinuclear antibodies and

complement are usually normal in PMR. The presence of antinuclear antibodies (antibodies that target

normal proteins in the body) indicates the presence of a disease in which the body attacks itself, which

PMR is not. The test for complement measures the activity of certain proteins in the blood, which play a

role in inflammation.

Some patients with PMR have elevations on blood tests that check the functioning of the liver, such as

AST (aspartate aminotransferase) and ALT (alanine aminotransferase), but usually the results are normal.

Another liver function test, known as alkaline phosphatase (ALP) can be mildly elevated in about 30% of

PMR patients, especially in those with giant cell arteritis that has been proven upon biopsy. Another level

function test, serum albumin (a protein made by the liver), may be slightly lowered in PMR. Blood tests to

check the functioning of the thyroid gland may be performed to rule out that symptoms are not being

caused by thyroid disease. The thyroid gland is a butterfly-shaped organ located in front of the neck that

produces a natural chemical known as hormones that affect virtually every cell in the body and many

functions such as disease fighting, heart rate, energy level, and skin condition.

Imaging studies

Imaging studies may be ordered such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and ultrasound scanning.

Ultrasound scanning is a procedure that uses high-frequency sound waves to produce images of internal

body structures. MRI scans produce extremely detailed pictures of the inside of the body by using very

powerful magnets and computer technology. The MRI and ultrasound scans are ordered in cases where

PMR is suspected to evaluate for inflammation of muscle tissue and the joints (in addition to sac around

the joints), especially in the shoulder and hip areas. For example, ultrasounds may show evidence of fluid

escaping from the sacs around the shoulder joints. MRI typically shows evidence of inflammation in sacs

around joints in the shoulder and inflammation of tendon coverings in the hands and feet. In PMR, an

abnormal finding on an ultrasound is usually found on an MRI and vice versa. In cases where fluid leakage

has been identified from a joint area, the fluid can be collected and analyzed which may reveal signs of

inflammation. X-rays are usually normal in PMR although they can show signs of arthritis.

There is evidence that positron emission tomography (PET) scans can detect inflammation of large blood

vessels in the hips, shoulders, and spinous process of the cervical spine (neck area) and lumbar spine

(lower back) in patients with PMR. PET scans involve injecting the patient with a small radioactive

chemical and being placed in a machine that detects and records energy given off by the substance. The

computer translates the energy into 3D pictures which provides information about how cells in the body

are functioning because normal cells react differently to the chemical than healthy cells. Spinous

processes are the bony parts that project out from the back of the vertebrae. Vertebrae are bones that

form an opening in which the spinal cord passes. Due to osteoporosis, women with PMR are five times

more likely than those without PMR to suffer a vertebral fracture.

Other tests

A biopsy (tissue sample for inspection and analysis) would not be helpful as the results are normal in

PMR. Electrical studies of muscle functioning are also negative in PMR.

Diagnostic criteria

Since there are no specific and definitive tests for PMR, the diagnosis is most likely when several

components are present at once including: being over 50 years of age, no other diagnosis present that

can reasonably explain the signs and symptoms present, morning stiffness (usually lasting more than an

hour), pain for one month or more in two of three of these areas (neck, shoulders, pelvis), a sed rate

higher than 50 mm/h, and rapid improvement in response to prednisone (30 mg or less).

In 2012, provisional criteria were set forth by the American College of Rheumatology and European

League Against Rheumatism for people age 50 or more who have shoulder pain on both sides and

evidence of inflammation (elevated C reactive protein and/or sed rate). These are not diagnostic criteria

but are designed to help select who to enroll in clinical research studies on PMR treatment.

Based on the above criteria, one point is provided for limited range of motion or pain in the hips. Another

point is provided for no peripheral joint pain besides the hips. One point can also be earned for ultrasound

scanning evidence of inflammation. Two points are given if the person has morning stiffness for more than

45 minutes. Another 2 points are given of there is no evidence on blood tests of a substance called

rheumatoid factor and/or anti-citrullinated protein antibody (anti-CCP). Rheumatoid factor is a type of

antibody that is often found in the blood of people with rheumatoid arthritis. Antibodies are types of

proteins that are formed by the body to destroy foreign proteins known as antigens. Rheumatoid arthritis

is a disorder in which the body's defense system attacks its own tissues, causing inflammation of bone

joints. Anti-CCP is a type of antibody directed against one of the body’s own proteins and is often found in

patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatoid factor and anti-CCP levels are normal in most cases of MR.

Based on the above criteria, a total of 7 points can be obtained. A score of 4 points or more will correctly

identify 68% of people with PMR. Seventy eight percent of people without PMR will not have a score of

four or higher. If using the ultrasound criteria, a score of 5 points or more will correctly identify 66% of

people with PMR and 81% of people without PMR will not have a score of 5 or more. These criteria can

be viewed here.

HOW IS PMR TREATED?

The main goal of treatment for PMR is to control muscle pain, muscle stiffness, and other bothersome

symptoms. Unfortunately, there are not many research studies where patients have been randomly

selected to receive one form of treatment or another to guide treatment in real world settings.

In terms of medications, PMR is treated with a low dose of oral corticosteroids which are medications that

help reduce inflammation and influence the body’s immune system response. Prednisone is the main

treatment choice for PMR as it is also known to decrease the amount of cytokines, which are proteins

that play an important role in inflammation. The starting dose is usually 15 mg a day but depends on the

patient’s weight and symptom severity level. If quick improvement (e.g., reduced stiffness) does not occur

in response to corticosteroids after two to four days, the person is unlikely to have PMR (especially if the

dose is more than 20 mg a day).

Many patients improve after only one day of corticosteroids but quick relief typically comes by day three.

The prednisone dose will usually be increased within a week after non-effective treatment. Some patients

improve more slowly, however, so some doctors will wait for 2 to 3 weeks of no response to

corticosteroid treatment before concluding that the patient does not have PMR. Once the symptoms are

under control (e.g., decreased pain and stiffness, especially in the shoulder), the dose of corticosteroids

will likely be tapered. This typically occurs after 2 to 3 weeks of corticosteroid treatment. Four weeks after

treatment with corticosteroids, improvement can typically be found on an ultrasound study. After the initial

monitoring of treatment in the first few days to weeks, patients with PMR are generally followed-up with

once a month until the dose of corticosteroids are tapered, at which point follow-up can be once every

three months.

The doctor will typically also regularly look at biomarkers of disease severity (e.g., blood test results, urine

analysis) to decide when to taper the medications but this not used as the main criteria to decrease or

stop treatment. Doctors do not consider a single increase in the sed rate as a reason to increase the

corticosteroid dose, but a temporary delay in reducing the dose may be needed. The medication is

gradually tapered rather than abruptly discontinued, because the body is sensitive to even small changes

in corticosteroid doses and this can lead to a relapse. However, treatment usually lasts more than a year

and sometimes up to three years. Some people may be able to stop taking the medication after 6 months.

The prednisone taper is usually about less than 1 mg a month until 10 mg a month is reached, at which

point the taper usually goes down by 1 mg every 2 months. Eventually, prednisone can reduce the sed

rate to normal. While corticosteroids are typically helpful, patients using them need to be frequently

monitored for serious side effects, especially if using the medication long-term.

Examples of corticosteroid side effects includes high blood pressure, high cholesterol, heart disease,

difficulty sleeping, bruising, thinning of the skin, weight gain, psychosis (detachment from reality),

cataracts, diabetes mellitus (and associated high blood sugar levels, which is why this is typically

evaluated via a blood test), and osteoporosis. Cataracts is a darkening of the lens in the eye. The lens is

an organ located between the colored part of the eye that bends light as it enters the eye. Diabetes

mellitus is a complex, long-term disorder in which the body is not able to effectively use a natural chemical

called insulin. Insulin's main job is to quickly absorb glucose (a type of sugar) from the blood into cells for

their energy needs and into the fat and liver (a large organ that performs many chemical tasks) cells for

storage. Osteoporosis is an abnormal loss of bone thickness and a wearing away of bone tissue.

To prevent osteoporosis caused by corticosteroids, the doctor may prescribe vitamin D or calcium

supplements, although some doctors believe these should be prescribed in all cases. If taking

corticosteroids for more than 3 months, the American Academy of Rheumatology recommends the

following daily doses: calcium (1000 to 1200 mg) and vitamin D (400 to 1000 international units). Calcium

and vitamin D levels in the blood may be checked by the doctor. The doctor may also perform bone

mineral density testing to monitor for osteoporosis before and during treatment. Medications known as

biphosphonates may be used to prevent osteoporosis caused by corticosteroids. Specific names of

medications used to treat osteoporosis includes estrogen, and risedronate (Actonel), and alendronate

(Fosamax). Vaccines for other medical conditions should ideally be administered before treatment with

corticosteroids.

Other medications used to treat PMR includes Methotrexate (Trexall) and anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF)

medications. Methotrexate (usually 7.5 to 10 mg a week) suppresses the body’s immune system which

can lower the dose of corticosteroid that is needed and preserve bone mass. When this medication is

used, it tends to be used for a year or more and the initial effects may take weeks to see. However, there

is limited data as to methotrexate’s effectiveness in PMR. For example, comparing the use of this

medication when added to prednisone in one study showed comparable results to patients treated only

with prednisone.

Anti-TNF medications reduce inflammation by decreased levels of TNF in the body, a substance that can

cause inflammation. The usefulness of anti-TNF medications varies from study to study but it may be

particularly helpful for patients who cannot tolerate corticosteroids due to side effects. One study found

that the anti-TNF medication, infliximab, showed no benefit.

Some doctors say that non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs) such as aspirin or ibuprofen

(e.g., Motrin, Advil) and naproxen may be used while on the maintenance or tapering phase of prednisone

for symptomatic relief (e.g., pain relief) whereas other doctors believe it is ineffective. Rarely do NSAIDs

offer complete relief and long-term use of these medications should proceed cautiously because it can

lead to kidney damage and bleeding in the stomach and intestines. NSAIDs may be used as the only

treatment in mild cases but it most likely does not help prevent progression of vasculitis.

Physical therapy is sometimes suggested to regain strength and improve the ability to physically perform

activities of daily living. Of course, eating healthy and exercising is also helpful to maintain bone and

muscle strength, strengthening the immune system, and warding off other health problems. Mild to

moderate exercise can improve pain and mood.

While exercise is important, being careful not to physically overdo it is also important. Choice of exercise

is important, such as ones that do not impact the joints harshly. Examples of good exercises include

swimming, use of an exercise bike, and walking. Stretching the muscles before and after exercise helps

keep the muscles and joints flexible. Always check with your doctor on the proper exercise regimen for

you. Many doctors will suggest about 30 minutes of exercise on most days of the week. Trying to avoid

strenuous tasks, or alternating them with less strenuous ones can be helpful. Use of physical aids such as

shower grab bars or other structural supports can place less strain on the muscles.

CAN PMR BE PREVENTED?

No, PMR cannot be prevented.

WHAT IS THE PROGNOSIS FOR PMR?

The prognosis for PMR is typically excellent (usually no serious complications) with prompt diagnosis and

proper treatment. PMR usually resolves by itself within one to two years, but patients who go untreated

tend to have a poor quality of life and feel unwell. Medications and proper self-care can improve the

recovery rate. Most people with PMR will feel much better two or three days after the first course of

corticosteroid treatment. Most people will need to continue corticosteroid treatment for one to three years.

The average person (50 to 75% of cases) with PMR needs treatment for two years. However, some

people need treatment with low doses of corticosteroids for several years.

Relapses in PMR are common, occurring in up to 25% to 50% of cases, especially in the first 18 months

of treatment (when the prednisone dose is less than 5 to 7.5 mg a day) or within one year of stopping

corticosteroid treatment. However, relapses have been known to occur more than one year after

treatment ends. This is why patients need continued monitoring for a year after treatment ends. When

relapse occurs, more treatment is needed, with corticosteroid treatment going back to the dose that

previously controlled the symptoms. Relapses are more likely to occur in people who taper off the

medication too fast. About 20% of patients have a relapse when tapering off the medication and about

10% of patients who successfully completed corticosteroid treatment have a relapse within 10 years of

initial treatment.

In some cases, permanent muscle weakness, loss of muscle mass (from disuse), and disability can occur.

In cases where PMR symptoms are associated with cancer, PMR improves with resolution of the cancer.

Patients with PMR are at risk for developing giant cell arteritis (a condition described earlier) which is why

they need to be monitored for this condition over time. In addition, there have been some cases of

amyloidosis occurring throughout the body related to PMR. Amyloidosis is when a protein known as

amyloid can no longer be dissolved and is deposited in spaces of different organs and tissues, disrupting

normal functions.

Provided that proper treatment occurs, death rates have generally not been found to be increased in

PMR. However, there is some evidence of increased death rates in patients with PMR due to diseases of

the circulatory system (the system that circulates blood) two years after diagnosis. This may be due to

uncontrolled inflammation throughout the body causing narrowing of arteries due to accumulation of fatty

substances.

WHAT IS THE ORIGIN OF THE TERM, POLYMYALGIA RHEUMATICA?

Polymyalgia rheumatica comes from the Greek word “poly” meaning “many,” the Greek word “mys”

meaning “muscle,” the greek word “algos” meaning “pain,” and the Greek word “rheumatikos” meaning

“subject to flux.” Put the words together and you have “many muscles (in) pain (and) subject to flux.”